How to cook a Musa Pseudostem August 6, 2008

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food, Humor.Tags: Banana tree, Bananas, Raw bananas, south indian cuisine

29 comments

C Y Gopinath discovers how to cook the delicious dish that killed the tender coconut tree but completely re-colonized his gut.

Take a medium-sized banana. Chop the pseudostem finely and boil till tender. Spice it and eat while costive.

There, that’s how you do it. I’ve given the recipe away. You can amaze your friends too now by making Banana Tree Khich Khach at home. They’ll laugh at you, of course, and nudge each other and whisper into their respective ears, ‘Goodness, he or she doesn’t know which part of the tree is the edible one. Next thing, he or she will be serving us Coconut Trunk Quiche.”

Don’t be daunted by the mockery, because all that will happen is that God will make them costive, and that will be the end of them all. When I was little my mother took me aside one day in my grandfather’s huge sprawling rubber estate in Kerala and said, “See these trees, son. Some of these are rubber, but a lot of these are banana. And every growing boy needs to eat a banana tree now and then. It is excellent for the bowels. The rough fibres of the banana stem act like a powerful broom, cleaning out the folds and crevices of your perineum.”

My bowels nodded agreement, and that was how I first tried out Banana Tree Khich Khach, for want of a better name.

I fell in love with it , and wanted to eat it every day. I told my mother, “Mother, mother, this stuff is so good for my bowels that I want more and more of it. I don’t want no banana fritters, I don’t want no bananas, I don’t want no banana leaf, all I want is some of that ol’ Banana Tree Khich Khach.”

“Once a month is all you get,” she said sternly. “No one should eat it more than once a month, and less than once a month is asking for trouble. Besides, it is a lot of trouble to cook, and I don’t love it that much. Overbesides, your bowels aren’t that bad.”

You can get banana pseudostems in Matunga in Bombay or Karolbagh in Delhi. They look like pale white plastic plumbing pipes, shiny and smooth outside, and usually cut into one-foot segments. I dialled my mother in Chicago and asked her exactly how much a person should buy. She’s terrible with quantities, like all mothers, and she thought for a minute, while the dollars ticked by. Then she said, “About one-and- a-half talcum powder tins, to feed about five.” How perfect – a banana pseudostem does resemble a cylindrical talcum tin.

Buy the banana pseudostem carefully. Check for discolorations – there should be none – and ensure that it is tender and white. Cutting it is an art best mastered through a little practice. Oil your hands, because the pseudostem exudes a sticky pseudo-goo that soap cannot touch. Peel away about two layers of the outer skin, about a centimetres depth, to expose the tender white rind within. This is the part you will cook and eat.

Cut into discs about four millimetres thick and plop into water. My mother’s voice whispers that you should add about half a cup of sour buttermilk to that water, to prevent the stem from getting discolored.

Here’s how you cook the stuff:

Ingredients:

1.5 banana pseudostems, prepared as described and cut into discs

1 cup tuvar dal

A little ural dal

A pinch of turmeric

A pinch of salt

1 tablespoon rice

3 or 4 red chillies

1/2 coconut, grated1/2 teaspoon mustard seeds

1/2 tablespoon jeera or cummin seeds

Finely chop the banana pseudostem. Pay attention to the lengths of ‘string’ that unwind as you cut. They should be assiduously removed and discarded.

Pressure cook the banana pseudostem, with one cup tuvar dal, some turmeric and some salt.

Take a tablespoon of rice, three red chillies, and fry in oil till just before the rice begins to redden. Grind to a paste with 1/2 the grated coconut

Combine this paste with the boiled banana pseudostem, add a little water if the result feels too thick, and then let the Khich Khach come to a boil over a slow fire. The banana pseudostem absorbs the various subtleties in the coconut paste, and emerges dressed for a party.

Throw a half teaspoon of mustard seeds into hot oil. When it begins to pop, add a half teaspoon of urad dal. As the dal begins to turn a lovely golden color, add a few whole red chillies, just for a few moments, and then throw the whole thing over the dish as a garnish.

It is now time to answer the question that has been distracting you.

What, you are wondering, is the meaning of the word ‘costive’, mentioned so casually in the first paragraph. No, it is not another word for the price index, but simply means — oh, I couldn’t possibly. Go look it up, everyone has Google these days. If you’re too lazy for that, try eating a little Khich Khach.

Read and see July 12, 2008

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food, Humor.36 comments

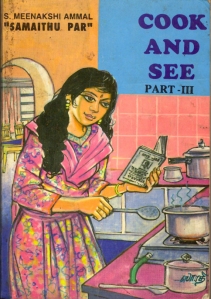

For decades, this classic set of three books has been the last word on authentic South Indian cooking, says C Y Gopinath

May I offer you some light tiffin? No? A cool drink then?

What about a curd bath? It’s guaranteed to cool you off.

According to the instructions in the third book of the Cook and See trilogy, the offer of a curd bath may fearlessly be made to Brahmin priests during certain auspicious days. The complete bath must include rice, buttermilk, sweet jaggery water, and a coconut chutney, among other things. Towels and soap are not mentioned.

Before you leap to the conclusion that this blog has degenerated into bathroom humor, what with the lavage of priests and all, let me add that bath merely happens to be how the venerable Meenakshi Ammal spells bhath, meaning rice, in her three-part classic set, Samaithu Paar (or Cook and See). As any self-respecting Punjabi knows, curd-rice is what gives the average Madrasi his or her keen edge and legendary stamina.

Similarly, both light tiffins and cool drinks are de rigueur when you are getting your daughted hitched to a suitable boy and the wedding guests are at the door. Page 162 of Book III goes further, offering a ‘List of Items Required for Preparing Food Etc’. In smaller type immediately below this are the words ‘For About One Thousand Persons’, followed by a list of 46 items that includes 12 kilos of coffee powder, 8 litres of ghee, 40 kilos of idli rice, and about 750 kilos of firewood.

Trust me, this is valuable information, available nowhere else on the planet but in S. Meenakshi Ammal’s revered trilogy. Spoken as it would be in Tamil, samaithu paar is a disarming invitation to try your hand at some fun stuff in the South Indian kitchen, make a few mistakes, create a complete balls-up of in all but on the whole have a very good time doing it.

If you are wondering, as you should be by now, where cooking comes into what has so far sounded like a one-stop marriage manual, the answer is Books I, II and III. I doubt there is any recipe or procedure featuring any vegetable or grain you can name that will not be found somewhere in these two volumes, starting on page 1 with four different ways of making sambar, and going on to such obscure but crucial life skills as the method for grinding Australian wheat into flour, preparing a perfect cup of south Indian filter coffee, and how to beat rice flakes into submission. For the latter, there is the helpful tip that “when two people pound it simultaneously by alternate strokes, the flakes turn out better”.

Samaithu Paar is simply the most authentic set of recipes I have ever seen on classic South Indian cooking. I was fortunate to find a fresh reprint at a Higginbothams book shop in Chennai. Amazingly, you will find its 1968 edition listed on amazon.com, but with a small line confessing that it is out of print. The single customer review there describes how indispensable it is to someone struggling to learn South Indian cuisine, even if navigating the book takes a little getting used to.

The books look today as they doubtless did when they were first printed in 1951. S. Meenakshi Ammal’s writing has not been value-added by the pens of modern recipe-makers. The ingredients and the instructions are offered in unhelpfully blocky paragraphs, no effort made to separate ingredients into lines. The tone of voice is that of an older woman advising a younger and inexperienced one. And this, it turns out, is pretty much what Meenakshi Ammal set out to do.

When she wrote her first volume, it was a planet that had not yet felt the need to coin a word like foodie. There was no great demand for cookery books, and no one thought it a great idea for a woman — imagine that! a woman! — to write an entire book of recipes. Meenakshi Ammal had many detractors and only a handful of supporters. One staunch encouraging voice was that of her uncle, father of the Library Movement in Madras State, the late Rao Bahadur Sri S. V. Krishnaswami. And her own indomitable will, of course.

The set I finally purchased had been revised by Meenakshi Ammal’s son, P. S. Sankaran, to include modern weights and measures rather than pinches and pugils and fistfuls. The publisher, in her introduction, explains:

“. . . it was also a time when with the opening up of more opportunities for women and the dawning of the realization that education was for both sexes, a vast majority of girls were not able to find the time to learn cooking in the traditional way from one’s mother. This proved a problem subsequently when, after marriage, they had to build their own homes and manage their own kitchens. In was to address this need that the author with a lot of foresight, embarked on her venture to bring out a cookery book which would serve more as a manual for daily use”.

Where a modern cookbook might have a single sentence, ‘Boil a cup of tuvar dal (pigeon peas) with turmeric’, Meenakshi Ammal has an entire paragraph, titled To Cook Dhal. It is vintage Meenakshi Ammal, cooking instructions as stream of consciousness, not a thing linear, afterthoughts interwoven with forethoughts:

Choose a stoneware of vessel with a very narrow mouth. Wash dhal. Clean and remove stones, if any. Boil water in a vessel. Add dhal, a pinch of turmeric powder and 1 teaspoon of gingelly oil. Cover with a lid or cup, filled with water. (Add this water to the dhal, if needed.) Cook till very soft. (If the dhal is cleanly husked, it need not be washed.) (Some dhals do not cook soon. If so, add a pinch of baking soda. If baking soda is added, do not use the turmeric powder, as the color of the dhal will be spoilt.)

Yes, I know. You want proof of the pudding. So here are three of my all-time favourites from her set. Not only are the recipes simplicity itself, but the spice mixtures I describe may be used for pretty much most other vegetables other than the ones I have described.

Potato Podi

Potatoes 350 gms (choose big ones)

Red chillies 6 or 8

Red gram dhal (tuvar dal) 2 tsps

Black gram dhal (urad dal) 2 tsps

Asafoetida (hing) a pinch

Black mustard seeds 1/2 tsp

Method

Fry the spice ingredients in 4 tsps of oil to golden brown color, and grind to a coarse powder along with 1 1/2 teaspoonfuls of salt.

Cook the whole potatoes in their jackets, and peel. Spread the spice powder on a board and place the potatoes on top of it. Press the potatoes with a roller to break them up. Keep breaking them up till the pieces are roughly the size of large marbles and thoroughly mixed with the powder. Serve with chappatis or rice, and sambar or dal.

Crumbled Arbi Curry

Arbi (colocasia) 250 grams

Juice of an areca-nut sized piece of tamarind in 1/4 cup of water

Whole black pepper 2 tsps

Cummin seeds (jeera) 2 tsps

Black gram dhal (urad dal) 2 tsps

Sprig of curry leaves

Salt to taste

Method

Heat a vessel with enough water to cover the arbis. When the water is boiling, add the arbis (washed and cleaned well) and cover with a lid. Turn it occasionally. When it is cooked, remove from the fire and peel. Cut each arbi into two or three pieces and keep aside.

Roast the whole black pepper, cummin seeds (jeera) and black gram dhal (urad dal). Grind into a coarse powder. This is known as curryma powder.

In a vessel, heat 4 teaspoonfuls of gingelly oil, and add a teaspoon of black mustard seeds. When they start spluttering, add the cut arbi pieces. Add about a teaspoon of salt and scald, turning frequently. Add the tamarind juice and boil till the raw smell of tamarind goes away. Add 1 to 2 teaspoons of curryma powder, curry leaves, and mix well. Keep cooking until the liquid has evaporated, and the arbis become a mass.

Serve with rice and dhal, or sambar.

And in closing, let me add that if some dedicated and selfless person were to take on the task of presenting the priceless recipes in Meenakshi Ammal’s books in a more user-friendly way with clear ingredient lists and instructions, and gorgeous drooly pictures as is the norm these days, on lovely glossy paper — why, I do believe there may be a modern classic here waiting to be lapped up.

Of course, you should make sure you have a word with P. S. Sankaran first. (more…)

Lessons from lasoon November 27, 2007

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food, Humor.29 comments

It might keep teenage vampires away but when you use it well in the kitchen, the unassuming garlic can unite the most diverse people

SMITH AND JONES GRIND GARLIC AT NASHIK. In case you think this is one of those phrases administered to suspected drunks to check their sobriety, it is not. Smith & Jones happened to be a brand of readymade garlic paste, one of latest products of ravenous, emerging giant India. I spied it on the mixes and spices shelf of one of the new breed of US-style self-service supermarkets in Mumbai.

Picked it up at once, of course, attracted by the Victorian-style graphics, the words ‘Traditional English Style’ written below in a pennant. Was this one of the newest Indian-made Foreign Imports coming out of a collaboration between a spirited desi entrepreneur and some expansive expatriate? Would Smith & Jones together wipe out Bedekar and Parampara? Was this the future of garlic, to be smashed and bottled and sold in disguise? Did Englishmen, by the way, eat garlic? Did Britannia rule with waves of garlicky breath? Hmmm.

I checked the fine print and discovered that Messrs. Smith and Jones operate out of a Nashik address, and instantly all was clear. Smith and Jones are probably the working names of some Sawant and Joglekar who have cannily realized that the future lies in garlic.

Made me start thinking about CYG and garlic. Allium sativa had not been a part of my strictly Dravidian childhood. Encountering it in Calcutta and Delhi, where I was shaped from boy to proud manhood, I felt formal towards garlic, like a Japanese towards a Gujarati. Gainda Singh, cook at my college , was a romancer of garlic, but since he shone in all other respects, I, as head of the Canteen Committee, tolerated this aberration.

When the corporate world tamed the garlic and bottled it as pearls, promising there would be no odour and yet the heart would glow with health, I checked that out. This is how garlic ought to be, I thought, unrecognizable, odourless, untastable, unseen. In brief, I was a garlic hater. I thought it behaved like the opposition in the lower House of Parliament, always disrupting proceedings.

I was wrong on all counts and today I stand ready to face the music.

The unforgettable Ishtiyaque Qureshi, ex-chef of the erstwhile Searock Hotel and later the Leela Kempinski, once fed me a kheer in which, I learnt later, the floating almond-like pods were really garlic. Garlic pudding! Aaaaargh. But it tasted somehow like a mild Lebanese paradise. “The trick is to subjugate the garlic by cooking it in milk long enough at the right temperature,” said Qureshi.

In Cairo, a taxi-driver’s wife ground raw garlic and green chillies together with salt and lemon juice, sandiwched it in the mouth of a small fried aubergine and fed it to me with whole fried Cornish chicken and a pasta salad. The one hero of this warrior-like meal was, believe it or not, the garlic.

Though my conviction that garlic was garlic was on the wane, for many years I maintained that it was best consumed in pearl form. Lest your social life take a plunge, you know.

But as of October 17, I have changed forever the way I perceive garlic. In large measure, this is because of a simple soup that was created by my wife Shilpa one sunset when no one felt like cooking and the evening stretched like eternity ahead of us. She threw a dart, it hit a Mexican cookbook, and another dart found page 72, Toasted Garlic Soup, serves 4 to 6.

“Don’t” I said, alarmed. “This marriage will be on the rocks!”

She ignored me. A woman who loves garlic knows what she wants.

I watched as she took a fistful of more garlic than I would have eaten in a month of Sundays, and toasted them. The aroma, forbidden and strong, filled the house. The child began to wheeze. The domestic help began muttering about paid leave. Then the vapours settled and more disciplined, suddenly more exciting, grew out of it. More things happened. I watched, face buried in my hands, nose twitching.

An hour later, I was tasting one of the most rogueish, ill-mannered and utterly charismatic soups I have eaten in a long time.

To get the entire recipe free of charge, all you have to do is click on the Bloggers Choice Award website link on top of this page and, only if you believe with all your heart that Gopium deserves one more vote, go and cast your vote.

On second thoughts, vote anyway. Who cares what you really believe in your heart?

On third thoughts, I’m not that kind of person. Here’s the full recipe:

INGREDIENTS

¼ cup cooking oil

1 large or even huge head of garlic, cloves separated, peeled and coarsely chopped

½ a baguette bread, cut diagonally into ¼” thick slices

4 medium-sized red tomatoes, peeled and seeded and coarsely chopped into chunks

7 cups stock (chicken, preferably, but Maggi vegetable cubes if you insist)

Salt to taste

½ cup thick cream

Method

1. Heat the oil in a large skillet until it is smoking. Add the garlic and stir over medium-high heat for a minute or so until the garlic cloves are lightly toasted. Transfer the garlic to a large soup pot.

2. Add as many slices of the bread to the skillet as will fit in one uncrowded layer. Fry over medium heat for a minute, turning once, until they are lightly golden on each side. Transfer to paper towels to drain. Continue until all the bread has been fried, and set aside.

3. Place the chilli peppers and tomatoes in the skillet and stir over medium high heat for a minute until they wilt. Transfer to the soup pot with the garlic. Add the stock and the salt, bring to a boil and simmer for 20 minutes, or until the garlic has softened.

4. Ladle the soup into individual bowls. Garnish each bowl with fried bread and a dollop of cream. Serve right away, piping hot.

Muri Blues November 27, 2007

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food.12 comments

There is a connection between young love and Calcutta’s jhalmuri

FROM THE DARKNESS OF KOLKATA’S LAKE GARDENS come the sounds of lovers holding hands.

Bet you’ve never heard the sound of lovers holding hands before, but I have. It’s not the usual slurps and slobs and chwoops and fevered whisperings, but more a steady chomp-chomp-chomp. Occasionally you might hear an intense burp.

It is the sound of two people deeply in love eating Calcutta’s jhalmuri together. No other city serves up this amazing snack based on puffed rice, or muri. The jhal refers to the fiery trail it blazes as it enters your system. Calcuttans buy their jhalmuri from numerous itinerant vendors who emerge towards twilight, with wicker baskets full of muri hanging from their waists. Arrayed around the basket like bullets in a carabinier’s magazine are old tins of ingredients such as rock salt, onions, green chillies and so on. If you took a closer look, you would find at hand a large Dalda tin as well, defaced and blackened, almost tired, in which he will combine the ingredients; and the small wooden baton with which he will give the mixture a twirl before serving it in paper cones rolled from old copies of Ananda Bazar Patrika.

Bengalis will swear that there is something almost magical about the old tin which imparts a fire-tinged magic to the jhalmuri and explains why home-made version can never match what lovers munch at Lake Gardens.

In the lane that runs by The Statesman building in Chowringhee, a gloomy hole-in-the-wall dispenses jhalmuri and nothing else. We used to despatch the office boy on late-work evenings to pick up jhalmuri. Putting aside crowquill and Rotring, we would shovel fistfuls of the stuff into our mouths, cursing at the fieriness of it and wiping the tears from our eyes. Work would be impossible later anyway, so we’d retire to some nearby beer bar and discuss the future of communism in Bengal.

Because it is based on puffed rice, you might mistakenly conclude that jhalmuri is probably a cousin of Bombay’s bhelpuri, but the truth couldn’t be further. If puffed rice is the gene pool, then jhalmuri is the warrior and bhelpuri the poet. The biggest mistake you could make would be to try and adapt jhalmuri to local taste, for that would not be murder, it would be assassination.

I spoke to several people, some of them Bengali, others with Bengal in their blood, to piece together the recipe for jhalmuri. Everyone remembered different ingredients, and I conclude that jhalmuri’s recipe itself must be variable. Accordingly, the recipe I give below lists the basic ingredients, and separately, a couple of add-ons.

[Do note, won’t you, that I could have insisted that you click on the Bloggers Choice Awards website link on top of this page and forced you to vote for this blog if you really wanted the recipe, but I didn’t, having too much character and integrity.]

INGREDIENTS

Basic

250 gms puffed rice (muri)

1 or 2 onions, finely chopped

2 or 3 spicy green chillies, sliced into fine ringlets

Half a cup of peanuts

1/4 coconut, sliced into slivers

50 gms dried peas (chana)

Boiled potato sliced into flakes

1/2 cucumber finely chopped

Rock salt

1-2 tsps freshly pressed mustard oil

Half a lemon

Add-ons

Raw mango cut into little slivers

Red chilly powder

My only caution to anyone experimenting with other add-ons is to remember that a fine line divides jhalmuri from other puffed rice preparations. On no account should you try to sweeten it, using tamarind water and the like, for that would bring it too close to the Maharashtrian counterpart. Similarly, do not add any ground spices such as aamchoor (dried mango powder) or garam masala — you might get interesting tastes but none of them will be the real thing.

Also, do note the casually used phrase ‘freshly pressed mustard oil’. Not only is this darker and more aromatic than the refined and packaged version, but it gives teeth to the jhalmuri plus it is what Calcutta’s muriwallas use. Whatever you do, do not, repeat, do not substitute mustard oil with any other oil except at your own peril.

You’re ready now. Bung the ingredients into an old magic tin and give it a good twirl with a wooden spoon. Squeeze some lime juice over it. Walk into a cosy dark spot with someone you love deeply, and start eating jhalmuri, occasionally holding hands or burping.

The sorry story of the uttappam October 6, 2007

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food, Humor.Tags: , dosa, Food, south indian cuisine

34 comments

The uttappam was feeling threatened by globalization — who am I? why does the pizza look like me? what should I do? C Y Gopinath counsels

It was a humid day, the sort that dampens all urges towards food.

I was sitting in my clinic, toying desultorily with some listless peanuts, when I sensed that someone was watching me. For a few years now — in fact, ever since parsley and iceberg lettuce began appearing in the local market — I have been running a small but successful practice counseling various culinary items who felt their identity threatened by the influx of Chinese, Italian, Lebanese, and Mughlai cuisines into India. My regular clients today include aloo chops wondering about the meaning of life after the MacAloo Tikkis; vermicelli upmas intimidated by chow mein; puri-bhaji that have been told that the railway platform now belongs to burgers; and others such paranoid entrées. I once had to make peace between some cloud-ear mushroom and a cabbage who feared displacement.

This particular evening, as the nation raced towards the millennium, I was certain I was being watched. I turned around, ostensibly to knock the ash out of my meerschaum, and casually glanced up. There it was. An unprepossessing uttappam about 10 inches across, it surface flecked with a few cowardly onion flakes.

“Ahem,” it cleared its throat. “I was wondering if you could help me.” I said nothing.

“It’s about the pizza,” it continued.

“What about the pizza?” I asked.

“Well, it’s pretending to be an uttappam,” replied the hapless dish. “But smarter. People think it’s an imported uttappam, and they go for it in a big way.”

I thought it was time to take this miserable little flip-flop in hand. “Listen,” I said. “You are an ancient rice batter preparation with history on your side. The pizza is a bread with some ketchup, odds and ends baked with cheese on top. How could anyone confuse you with that?”

Trouble started, said the uttappam, when the Udipi restaurant owner began to sprinkle Amul cheese over the uttappam just before frying it. The cheese would not melt or brown over, but merely turn a little crisp. “We were humiliated,” said the uttappam. “No one has done that to us before. And it’s all because the pizzas are baked with Mozzarella.”

In the meantime, atrocities were being committed upon the uttappam’s cousin, the dosai. The Dosa Manchurian was invented in a small tattukada in Cochin, in which the dosai was made to hold its own weight in chow mein, instead of the usual warm spiced potato mash. Indeed, every conceivable filling and covering was being indiscriminately inflicted upon the dosa — from heron’s egg omelettes to prawn malabari to chicken dopiaza to vegetable stew. The dosai was so crushed by these assaults that it surrendered its identity meekly.

Even Chinese cuisine, once Chinese, latterly Indian, and now victim of the Indian cook’s attempt to please all and sundry, was being mauled. In a small eatery in Mumbai, I had myself tasted the Chow Mein Manchurian Mussallam, in which finally the mainland meets the hinterland in a clashing war of opposite tastes. All lose, only the cash register wins. I had beheld horrified the dawn of the Hakka Afghani, the Tandoori Croissant, the Amritsari Upma, with chunks of Reshmi Kebab in it.

I even understood why it was going on. This country could not stand globalisation. The Indian abroad hides behind papads and garam masala. The Indian at home carefully checks the ‘imported’ dishes coming in through Immigration, and then cleverly renders them insignificant by ‘adapting’ them. The adaptation process is simplicity itself — he must sprinkle garam masala over it, substitute ghee for olive oil, rev up the red spices a little and sprinkle the dish with coriander just before serving. The pizza thus vandalised could be fashionably re-named La Pizza Indiana, and be hailed as a triumph of thinking global but acting local.

My wretched uttappam was sniffling. “What shall I do?” he moaned. “I have lost my self-respect.”

An idea struck me. “You have lost nothing,” I said firmly. “You have only gained. Listen carefully: the pizza is undergoing deep changes. I expect that its base will soon be substituted by a thick dough of rice and lentils. Tomatoes may become optional. This is your chance: you must strengthen your foundation with a strong baking dough made from good baking flour. I want you to welcome all sorts of toppings, even non vegetarian ones. Don’t flinch under bacon or tuna or ham or mince. And when they bake you, smile as though you love nothing more.”

“But — but —“ spluttered the uttappam. “I won’t be an uttappam any more!!”

“You won’t, perhaps,” I said reasonably. “But the pizza will be the uttappam. The more it resembles the uttappam the bigger the market for it.”

“And I? What will I be?” whined the uttappam.

“Why, you silly little pancake,” I said, my patience snapping. “You’ll be a pizza, of course. You’ll be the king.”

A chip of the old Nayak June 28, 2007

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food, Humor.18 comments

In a clear case of judicio-culinary activism, C Y Gopinath is put on trial for declaring Rama Nayak’s wafers to be the best in the universe as we know it.

Yes, M’lud, I am reasonably certain that it was not an Indoor Locker.

Or Indoor Laukar, as they tell me its erroneously called in the teeming wholesale veggie markets of downtown Maharashtra. Or Indore Locker, for all I know. In fact, Your Grace, your best money won’t get you a decent Indore Locker till after Christmas is gone and you’ve rung the new year in. After that, it’s Indore Locker season all the way till May, with the occasional Talegaon showing up.

But if it’s December — and it will soon be — then the potato of choice for frying wafers is not the Indore Locker or the Talegaon but the Mahabaleshwar potato. And I stand guilty as accused of having declared, in a public place and in a loud voice, that the wafers made at Rama Nayak’s 50-years-plus Udipi Hotel, just outside Matunga East station, deploying the magnificent Mahabaleshwar, are the best in this quarter of the universe. Or at least the Asia-Pacific rim.

All I ask, before this august court sentences me to a lifetime of dry dum aloo with no spices, is a chance to defend myself.

The problem, Your Excellency, is that you’ve never held a Rama Nayak potato wafer between your grubby judiciary fingers, else you wouldn’t be trying me for nepotism. It’s really very thin, you know. Wafer-thin would be the exact phrase that’s eluding me. Hold it up against the sun, and God will shine a light through it, coming out all translucent and glorious on the other side. In color, it will be a uniform pale gold, though the occasional one will be streaked with a reddening that got past quality control.

Pop one in your mouth and close your eyes as you chew. It’ll crumble all crisp, like the credits of some modern movie, releasing only texture and a fleeting certainty that nothing is wrong with the world at the moment. The feeling disappears in an instant along with the wafer, but if you want it back just pop the next one in your mouth.

They come in packets of Rs.20 each, Your Rectitude. They are not vacuum sealed or foil packed. And they are completely touched by human hands every little inch of the way.

One the day that I took it upon myself to personally inspect the wafer-making process at Rama Nayak, the human hands in question belonged, respectively, to Ratnakar, potato peeler from Kundapur, South Canara; Uday, potato slicer from Bhatkal, on the border between South and North Canara; and Ramaiah, deep fryer from Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu.

It is nearly a religious experience, Your Wittiness, watching wafers being made. The Mahabaleshwar is a sturdy, soldierly potato with a parched-earth tracery on its red-brown skin. Early in the morning, Satish Rama Nayak, who runs the show, or his nephew-in-training Pravin Kumar, will already have chosen the best Mahabaleshwars in the market, going by shapeliness, girth, and absence of sprouting eyes and discolorations.

“Plus hardness,” says Satish. “A good Mahabaleshwar is full of water, which makes it hard. Soft potatoes go phut so we try to retain the water but get rid of the starch.”

Starch is enemy number one in Waferland. It makes the wafers stick to each other, it absorbs oil, it creates grease and glaze, and it causes, eventually, cardiac arrest in loyal customers. After being peeled, Rama Nayak’s Mahabaleshwars are dunked in cold water for two starch-sucking hours. Then, after Uday the potato-slicer has done his stuff, they do two more hours in a metal tub, where they float pale white and luminous like dream flakes. This water will presently grow milky with starch, while the wafer, losing weight, gains a certain formal bearing.

And it’s ready to boogie.

It will not have escaped your sharp notice, Your Perspicacity, that potatoes start cooking at 113°C but brown at 188°C. It might, however, never have crossed your fine sub judice mind to ask how on earth they measure temperature in a 50-year-old Udipi kitchen without thermometers? I’ll tell you, m’lud. The deep-fryer from Tirunelveli sprinkles a little water on the oil. If it merely crackles unhappily, then the oil isn’t hot enough. If, instead, it shatters the airwaves with a resounding whipcrack, then it is ready to host the Mahabaleshwars.

Into the wok they go. There is a celebratory effervescence as the wafers begin to surrender their remaining water. Then, for exactly three minutes, they jostle around happily like tourists in a 5-star jacuzzi, getting their hides lightly tanned.

They out they come. The surface oil drips away into a colander. Ceiling fans are switched off lest the wafer start losing confidence. There is a light summer shower of salt, sometimes red chilly powder as well. And Ratnakar the potato-peeler turns into Ratnakar, wafer-packer. Does about 60 packets a day. No bulk orders accepted, now or ever.

Your Pulchritude, I’m all admiration for your gush of judicio-culinary activism, pressing charges against a harmless wafer fetishist like myself just because I feel kindly towards Rama Nayak’s wafers, but do you really have a case? Here, try one of these. Want another? Go for it. What about this spiced one? Don’t close your eyes, Your Magnitude. Concentrate on the accused. You have a case to judge.

And you should really stop this injudicious slurping.

And don’t speak with your mouth full.

Your Honour.

The future of Gobi Manchurian March 4, 2007

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food.9 comments

It turns out that Manchuria was unaware that its name had been appended to the phool gobi. When the news leaked out, all hell broke loose, reveals C Y Gopinath

“WE HAVE NO CHOICE,” said the Manchurian National Security Advisor. “This must be considered an act of war. By annexing Manchuria to a cauliflower, India has breached every protocol known to international politics.”

There was silence in the conference room. Though the new millennium was well under way, the temperature outside had not changed; it remained –26°C. The heating system was yet to be installed, so it was shivering cold inside as well. The only one unaffected seemed to be the shaggy horse on which the Manchurian Premier had arrived; it now stood in a corner of the room, attacking fodder while snorting and farting by turns. Other than the Premier, there were also his three military chiefs, his Press Advisor and the Minister for Foreign Affairs, who had built up the case against India.

At the far end of the table, leering openly, sat the Indian delegate, MLA Ram Lakhan. He drew himself up to his feet, emitted some paan into his portable paandaan, and spoke up now in his country’s defense.

“This is nothing but a small misunderstanding, Your Honor,” he said. “We do not have Chinese cuisine anywhere in India.”

“A complete fabrication!” said the Minister for Foreign Affairs. “Let the Indian delegate explain how I have seen the so-called Gobi Manchurian served only at labeled Chinese restaurants all over India?” As Exhibits A, B and C, the Minister now placed some quite cold and congealed specimens of Gobi Manchurian gathered from restaurants in Tangra (Calcutta), Colaba (Mumbai) and Ludhiana (Punjab).

“The Honorable Minister is in error,” said the Indian delegate mildly. “Those are not Chinese restaurants. Those are actually Punjabi Mughlai restaurants which specialise in South Indian cuisine. Within them, you can get such historical delicacies as Mattar Paneer, Methi Chaman Bahar, Chicken Makhani and Maharani Dal, in any combination with Masala Dosa, Cheese Uthappam, Medu Vada and Kanjeevaram Idli. There is nothing Chinese about any of them.”

The Minister for Foreign Affairs withdrew Exhibit D, the signboard of a shop that had recently come up in Girgaum, Mumbai, for a multi-cuisine restaurant called simply Buckingham Palace. All kinds of Mughlai, South Indian, Punjabi and Chinese food available.

“Another grave error,” said the Indian delegate, sniggering. “We say Chinese so that our customers may know that the waiters are Chinky-looking. We recruit them from Darjeeling, the Kumaon hills and so on. Gives the place an international feel.”

“Lies!” shouted the Minister.

“And nothing Chinese about anything else in our restaurants either,” continued the MLA equably. “We may call it Prawn Sichuan , but it is garnished with black mustard seeds and curry leaves, so that our Mangalorean clients don’t find the taste too alien. We also add a little garam masala to our Roast Lamb Hunan Style so that our clients from the film industry feel at home. In fact, in Chennai, a little sambar powder and coconut is added to all chow meins so that the local sensibilities are not offended.”

There was a silence. “Then why bring Manchuria into it?” asked the Premier gently.

“The dish in question has never been called Gobi Manchurian, but Gobi Man Churaya,” explained the MLA. “In Uttar Pradesh, from where most of India’s leaders emerge, this is a phrase meaning steal one’s heart away. Gobi Man Churaya refers, simply, to a cauliflower dish that can steal your heart away. In fact,” the MLA said, suppressing a snigger, “we were not even aware that a country called Manchuria existed till we got your letter.”

The Manchurians rose to their feet at this gross insult and rejection of their sovereign wilderness. “In that case, Mr. Ram Pal, we have no choice,” said the Premier. “It is war. You have defiled our cuisine, now we must desecrate yours.”

Historians note that in the decades that followed Manchuria avenged themselves by launching Sambar Cantonese (featuring hoisin sauce instead of tamarind and five-spice powder instead of chaunk ); the Beijing Baingan Bahar (in which the aubergines are buried for six years before being cooked and eaten), the Soy Bean Masala Lassi; and finally the Ming Biriyani, cooked in the purged stomach of a Chinese running dog of capitalism for five hours.

The Indian MLA, history has it, went back and victoriously reported to his masters that Indian cuisine had once again expanded its frontiers and invaded Manchuria as well.

The sous chef passes a fishy test March 4, 2007

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food.2 comments

‘WE’RE HAVING A SEAFOOD FESTIVAL!’ said the voice from Bombay’s SeaRock Sheraton, in the good old days before the bomb blast that closed it down. “We thought you might be interested in covering it in your amazing blog, Gopium!”

This meant that I was being invited to check out some free food at a 5-star hotel, you understand. On such matters as pre-paid gifts from corporations, or sponsored junkets to foreign countries, I have always followed a strict policy of reluctant acceptance in a Marxist frame of mind, which means that I say yes, infiltrate the system and destroy it from within.

Accordingly, I shook my head slowly from side to side into the phone, and said, “I am afraid that would be out of the question. Gopium does not concern itself with food festival reviews. It is a food column for the particular but not particularly rich reader, and it is compulsory to reveal at least one complete recipe The dish must be impossible to find in any book. It must contain ingredients that are impossible to predict. Occasionally, the exotic and the experimental are permitted, but on no account must the item be daunting and intricate. Thus, while I am perfectly willing to come and sample your seafood at a time and date convenient to me, the chances are that I will find nothing worth writing about.”

I was right. There was nothing worth writing about. There was an unremarkable mackerel which I could not even eat. There was a very good warm seafood salad, but it fell short of Gopium norms of exoticity. There was an excellent bream, stuffed with sundry things, I got the head, my companion got the tail, both were outstanding, but the item was too complicated for the average but avid cooking enthusiast.

This was when I addressed the Sous Chef, a young, faintly Gallic-looking fellow, and explained about Foodophilia. The Sous Chef, who had been forced by Saddam Hussein to leave his job with an Oberoi hotel in Iraq and return to India, was personally in charge of SeaRock’s Seafood Festival, and was evolving quite a few unfettered combinations by mixing old ingredients with new ideas.

“Why don’t you create a special dish exclusively for my column, and then put it into your menu as the Chef Recommends special? Why don’t you include in it ingredients that no one would expect to find in a fish dish — such as, say for example, say for example, ajwain? Something like that, do you get my drift?”

Three days later, I returned to the scene of the crime after receiving word that the Sous Chef had done something that should be attended to without delay. It turned out he had done four different tricks with fish, just to be on the safe side. The one I reproduce here will make your senses quicken to an unexpected glimmer of ajwain. The fish is a modest one, bekti, designed by God to alleviate every spice and flavour that falls upon it, and by God, the Sous Chef has managed to do bekti a flavour it will never forget. Before I present Paupiette of Bekti in Coconut, Lemon and Saffron Sauce, I hereby rename it

Bekti avec a touché of ajwain et other things

Serves 4

INGREDIENTS

8 Thin fillets of Bekti or rawas

16 medium-sized spinach leaves

The Marinade

Juice of 2 lemons

Salt to taste

3-5 gms white pepper

Cling film or silver foil for wrapping the paupiette

The Stuffing

480 gms prawn mince

80 gms finely chopped onion

15 gms garlic

3 to 5 gms ajwain

80 gms grated cheese

2 tomatoes

2 tsps finely chopped green coriander

30 ml butter

Salt to taste

The Sauce

200 gms coconut cream from tender coconut

1 gm saffron

4 blades lemon grass

45 gms butter

30 gms flour

300 ml fresh cream

2 litres fish stock for poaching paupiettes

2 tsps finely chopped green coriander for garnish

THE METHOD

1. Take a large fillet of bekti, trim sides and belly area. Slice thin, by cutting across the fillet at a slant with a very sharp knife. Marinate the slices in lime juice, salt and pepper, and keep in a fridge.

2. To prepare the stuffing, clean, de-vein and wash the fresh prawns, and then mince them. Chop two large onions fine, and peel and chop the garlic pods. Wash and chop the dill and the coriander leaves. Blanche the spinach leaves and refresh them in chilled water. Cut the tomatoes into quarters and discard the pulp, and cut the flesh into small pieces. Grate the cheese finely and mash with your bare hands, and then roll them into thick ‘straws’ by rolling them between your palms.

3. Heat the butter in a pan and bung in the ajwain. Add the chopped garlic after a few seconds, and finally the chopped onions, which should be sauteéd till they turn transparent (or for three minutes, whichever comes first).

4. Now add the minced prawns and mince and sauté lightly, making sure the juices do not run out. Add salt to taste, remove from flame and keep aside. When it has cooled, add the chopped coriander and tomato pieces, and mix. Divide the stuffing into eight equal parts.

5. Take a slice of bekti and put two leaves of blanched spinach on it so as to cover it. Spoon some of the prawn mince onto this, and place a ‘straw’ of cheese in its centre. Roll it up — fish, spinach, prawn, cheese and all — wrap it in cling film or silver foil, and twist the ends together like a toffee. After cooling it in a fridge for a while, poach the paupiette in the fish stock.

6. To prepare the sauce, pureé some grated coconut, strain to recover the cream, and keep aside. Melt butter, add flour and cook for three minutes or so, till the aromas of cooked flour are released. Add the cream, and the lemon grass blades, and simmer for two minutes. Add the saffron strands. Once the mixture acquires the saffron colour, add the coconut cream, bring to a boil, and then simmer gently for two minutes. Strain.

7. To assemble, pour the sauce on to a heated plate, cut at a slant and arrange the paupiettes in the sauce. Between the fish pieces, sprinkle the finely chopped coriander coriander. Carrots and cucumbers may be arranged on the plate, says the Sous Chef, as vegetables-in-waiting.

I am not going to reveal to you the recipe for Fillet of Sole Rothschilde, also a creation of this amazing Sous Chef. My reasons for this are natural reticence, a strong perverse streak, and an amazing shortage of bandwidth.

Don’t curry, be happy February 21, 2007

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food.18 comments

A South Indian, a Punjabi, a Frenchman and an old East India Company hand meet to figure out what curry really is. C Y Gopinath was a fly on the wall

ONE DAY, APPUSWAMY, CHOPRA, SMITH AND BEAUVILLIERS finally met to thrash out a matter that had been troubling serious cooks all over the world: what was the correct recipe for the world-famous Indian curry? Each was a curry expert in his own right, and each disagreed vehemently with the other three.

Appuswamy staunchly maintained that the only place on earth where real curry was South India, and that it was spelt cari.

Chopra claimed that it was actually spelt kadhi, and was a delicious preparation featuring spongy chickpea flour dumplings in a buttermilk-based gravy.

Smith, who claimed it was his real name, said that England had countless Indian curry restaurants, adding that he had eaten in them all. “At least one of them must be serving genuine Indian curry,” he argued.

Beauvilliers would generally burp and hold his peace, as though what he knew could not be shared with commoners.

I knew trouble was brewing when Appuswamy one day produced a dark green tin labelled Original Madras Curry Powder. “Woriginal!” he spat out. “Myself woriginally from Madras. We are not having any such powder. It is a plot.”

“But old fruit,” said Smith patronisingly and with galling logic, “how could you possibly not have it? It says right here in big letters ‘MADRAS’ — so it stands to reason that it must have come from Madras. N’est-ce pas, old frog?” The last line was addressed to the lofty Frenchman.

Beauvilliers burped off-handedly, which Chopra took as his cue to reveal more virtues about Punjabi kadhi. “In Bhatinda,” he confided, “they put double hing in kadhi. It is the secret why girls from there make good wives.”

Finally, of course, they had to call me in to settle the dispute. I, in turn, lugged in my trusted copy of the Larousse Gastronomique. “Curry, gentlemen,” I began reading, “is a dish flavoured and coloured with a mixture of spices (curry powder) of Indian origin. In India, the ingredients of curry vary according to the individual cook, the region, the caste, and the customs.”

I stopped. Clearly this was a circular definition. According to this, anything cooked in India or by an Indian or with Indian spices could be called curry. Curry was all things to all people. Everybody wins.

“This is a bleddy nonsense written by some French porukki,” rumbled Appuswamy. “In the south, curry is cari and it is not having any spices.”

Chopra looked miffed that curry had been spelt with a ‘c’ again. “In Ludhiana, they eat kadhi three times a week. That’s why the men finally sing on Channel V.”

Smith, tiring of this Third World balderdash, spoke with the air of one settling the issue once and for all. “I say, old fruits,” he said, “sorry and all that, but you simply mustn’t think curry as we know it has anything to do with India, you know. In the Westend, where the best curry places are, we categorise curries as mild, hot and very hot. A standard British curry would contain turmeric, coriander, cumin, cloves, cardamom, ginger, nutmeg, tamarind and chili pepper, and sometimes fennel, caraway, ajowan, mustard seeds, cinnamon —”

“Yes,” said Chopra eagerly. “We make this in Amritsar also but we call it garam masala.”

Appuswamy blew his nose in disgust. “Not a spice powder, saar,” he said. “Yit is a circus. Ye yabomination.”

“Excuse me,” I said to Smith. “How do you know so much about Indian curry powder?”

“Bloody ruled you for years and years, didn’t we?” he said. “Don’t forget, we and the Dutch are the ones who made curry famous over Europe. And if there was a fixed formula for curry powder, you can thank the East India Company for it.”

Beauvilliers stirred. France, land of fussy gourmets, was going to speak. “Messieurs et dames,” he said. “I zink you know who I am. Ze famous Beauvilliers. My father is ze one who, in 1814, proposed the first official recipe for curry powder. But it was in 1889, at the Universal Paris Exhibition, that the composition of curry powder was set by decree. Please remember, France is the home of the ISO standard. When we say thees ees eet, eet ees eet. Voila.”

He proceeded to detail the official recipe for Indian curry: 34 gm tamarind, 44 gm onion, 20 gm coriander, 5 gm chilli pepper, 3 gm turmeric, 2 gm cummin, 3 gm fenugreek, 2 gm pepper and 2 gm mustard.

“Zat ees what we in the west call curry powder,” said Beauvilliers, with a fey flourish.

With that, India’s least known contribution to western cuisine, disappeared from our land forever. Appuswamy, shocked out of his Dravidian wits, sat stunned.

It was Chopra who finally broke the silence. “Main keya,” he said in good Chandigarh brogue, “why worry, dear? It’s only curry.”

The Royal Picnic of the Full Moon February 21, 2007

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food.2 comments

In a certain month of the year, the Pandiya kings of the south changed into gourmets under the full moon, discovers C. Y. Gopinath

WHAT DID GOOD SOUTH INDIAN PANDIYA KINGS do on full moon nights in April?

According to an unusually reliable source, they would take their wives and children to the riverside and have a great old picnic. While the moon grew fulgent and gravid in the sky, they would entertain themselves in kingly ways, singing old kingly Pandiya songs, telling Pandiya tales of valour and conquest, and finally, in a frenzy of Pandiya hunger, eat some royal Pandiya food.

This royal picnic fare, whose precise cooking details have just reached me, would have been prepared to exacting specifications earlier that April day. Because it would almost certainly be quite cold, or at least tepid, by the time it was dished out, it had to be conceived so as to be quite delicious even when cold.

Because of the unelectrified lunar light it would be served by, the food had to be independent of visual appeal. It had to be dry and gravy-free but should not render royal gullets arid during its passage. It should not require consumption in any particular order, nor call for any particular accompanying dish.

Finally, it should please a king.

The cuisine that met all these criteria was called chitrannam, and carried to the riverside during the month of Chitra (14 March to 15 April) on the day of Chitra Purnima (which, by the way, just passed us all by on 15 April). As I write this, the next full moon is on 15 May, and that too will be a thing of the past by the time you read this. However, 14 June is not far.

Chitrannam is made entirely from rice.

The things Pandiyas did to glorify rice, without recourse to a single vegetable or meat, surpass the merely amazing. A typical Pandiya picnic hamper might have included tamarind rice, lemon rice, coconut rice, sesame rice, mango rice and curd rice (and, of course, some payasam or kheer to sweeten the aftermath). In addition, there would have been papads, and perhaps pickles. I had best get down to details now, as each rice is slightly different in its preparation.

The basic chitrannam is boiled rice with a certain garnish. However, because the garnish varies marginally between the recipes, you have to prepare each rice separately. Also, the red chillies in the garnish merely add pungency, so do modulate their quantity according to taste. Below, I furnish the recipe for the basic garnish; with each recipe, I will indicate the ingredients that must be left out or added to the garnish. Finally, there will be the special ingredient — lemon, sesame, coconut and so on— that will distinguish the rice.

Of the six recipes, tamarind rice is unique in requiring a special gravy to be prepared in advance, so I have provided this recipe last of all.

Basics

To make rice to feed 4-6 people

3 kgs of basmati rice

3/4 sprigs of curry leaves, finely shredded

2-3 tbsps unrefined sesame oil

Salt to taste

Boil the rice, and let it cool a bit. Add the curry leaves, salt and oil, and mix it into the rice with a wooden spoon. Break it into roughly six parts and keep aside.

Garnish

2 tsp mustard seeds

1 tsp chick peas (chana ka dal)

1 tsp urad

4 sprigs curry leaves

1/2 cup of unrefined sesame oil or ghee (clarified butter)

10-12 red chillies (or according to taste) broken in halves

Heat the oil, and then throw in the mustard seeds, chick peas and urad. When the mustard begins to crackle, add the curry leaves, red chillies (and any additional ingredients as indicated with each recipe). Stir the mixture for a while, and then add the rice. Salt to taste. Mix it all together well with a wooden spoon. This garnish must be prepared afresh for each recipe below; certain additions and subtractions must be observed as indicated.

1. LEMON RICE

Garnish (as above)

Use sesame oil

PLUS

A fistful of cashew nuts, broken into bits

3-4 chopped green chillies

A little chopped ginger

1/2 tsp turmeric

Juice of about 4 lemons

Prepare the garnish, throw in the rice, stir awhile. Remove from the fire, and add the lemon juice. Mix well.

2. COCONUT RICE

Garnish (see above)

Use ghee

PLUS

A fistful of cashew nuts, broken into bits

3-4 chopped green chillies

A little chopped ginger

1 coconut, grated

Prepare the garnish, and keep stirring till the grated coconut and the cashew nuts begin to brown a little. Throw in the rice, stir awhile. Remove from the fire, mix well, and keep aside.

3. SESAME RICE

Garnish (see above)

Use ghee

PLUS

3-4 chopped green chillies

A little chopped ginger

MINUS

Red chillies (leave out of the garnish, or reduce in number, as they are part of the powder)

Make a sprinkling powder using

1 cup sesame, roasted

10-12 red chillies, or to taste, roasted

A small cube of asafoetida, roasted

Prepare the garnish, and when it is ready, throw in the rice. Stir awhile. Sprinkle the sesame-red chillies powder. Remove from the fire, mix well, and keep aside.

4. MANGO RICE

Garnish (see above)

Use sesame oil

PLUS

3-4 chopped green chillies

A little chopped ginger

1/2 tsp turmeric

1 raw mango, cut into small bits

Fry the mango shreds in hot oil for about 2 minutes, and then keep aside. Prepare the garnish, and when it is ready, throw in the rice. Stir awhile. Sprinkle the fried raw mango bits. Remove from the fire, mix well, and keep aside.

5. CURD RICE

Garnish (see above)

Use sesame oil

PLUS

3-4 chopped green chillies

A little chopped ginger

1/2 tsp of methi (fenugreek)

A pinch of dry ginger root, powdered

A small cube of hing, soaked in water for about 30 minutes

2 cups of fresh milk, lukewarm

1 cup of fresh curds

Prepare the garnish, and when it is ready, throw in the rice. Stir awhile. Remove from the fire, mix well, and keep aside to cool. Add the milk, curds, sprinkle the ginger powder and the water the hing has soaked in. (If you’re wondering why, the answer is that the Pandiyas were wondrous wise. They knew that if they used pure curds alone, the rice would have soured before it was eaten.)

6. TAMARIND RICE

To make the tamarind gravy

Garnish (see above)

Use sesame oil

PLUS

1/2 tsp of methi (fenugreek)

A fistful of shelled peanuts

1 lemon-sized ball of fresh tamarind

Grind into powder

4 tsps sesame seeds, fried in a little oil

A small cube of asafoetida (Hing), fried in a little oil

Soak the tamarind in warm water for about five minutes, and then squeeze out the juice. Keep it aside.

Prepare the garnish as described above, including the peanuts and methi with the other ingredients of the garnish. Add the tamarind water, and salt to taste. Simmer the mixture till it thickens somewhat. Sprinkle the sesame seeds powder over the thickened tamarind gravy. Add the boiled rice to the tamarind gravy, mix well with a wooden spoon, and keep aside.

I have early childhood memories of chitrannam, though we called it a vennila picnic — or White Moon Picnic — because it was not the month of chitra and besides, we were not Pandiyas. Only once was the venue faintly reminiscent of a river. We rented a boat at Delhi’s Boat Club lawns and rowed down the man-made waterway just about wide enough to catch a full moon’s reflection. An uncle rowed, his ebony biceps rippling, and my mother served that wonderful food. Bats flitted about peacefully, night owls chuckled, and we yawed and pitched gently, eating, eating, eating.

The Syrian Christian coconut February 21, 2007

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food.6 comments

C Y Gopinath presents a possibly imaginary sweet that is made only once a year by certain Keralite families no-one seems to know about

ONCE UPON A TIME, long ago, in the enchanted part of India known as the Backwaters, there lived a simple villager named Mohan. Thin but wiry, with jet black hair and intense eyes, Mohan had one great passion — cooking. It was widely acknowledged (or at least undisputed in the stretch of the Backwaters where the Onam Boat Race is held annually) that when it came to wizardry in the kitchen, there was nothing even Mohan’s mother could have taught him.

Whenever there were visitors to his part of the waters, Mohan would brusquely shoo away the womenfolk and take over their kitchen. The women, who knew they would never be a match for Mohan, would outwardly mutter and groan and feign inconvenience as they left. Later, after he had conjured up a perfectly magical feast, Mohan would summon them to serve the food. He himself would modestly retire to a vantage behind some coconut tree, probably to study the expressions on his guests’ faces as they ate.

The thing that I do not know about Mohan is whether he was capable of cooking up recipes in his head as well as in the kitchen. Some cooks are like that, you know. They can effortlessly imagine into existence a dish that perhaps no-one could possibly ever make.

And this is why today, nearly six years after I met Mohan, I still do not know if the Syrian Christian Coconut is for real or something Mohan dreamed up to make me smile as I left Allepey.

It was a film shoot. It was a hot and humid day, with bright, clear sunlight and sweat glinting on foreheads and knuckles of the unit members. Lunch, when it was finally served on plantain leaves in a shady backyard, was a welcome break.

As the women bustled about, tittering courteously and serving, I began to wonder who among them had created such amazing food. There was a dish featuring mussels and yams in a coconut gravy; another featuring jackfruit and tiger prawns; a sort of spicy sambar; crisp fried tapioca wafers. And that was when Mahesh Mathai, the film’s director, introduced me to his friend Mohan.

Mohan spoke no English, and I barely understand Malayalam, but when people are united by affection for the craft of good cooking, words hardly pose a barrier. In the boat on the way back to Cochin, I used an interpreter to probe Mohan’s love of cooking.

His answers, it seemed to me, were somewhat distracted, as though he had some more urgent mission. Suddenly he asked me: “Shall I tell you about the Syrian Christian Coconut?” And that was how it unfolded.

Once a year (said Mohan), just after the paddy harvest, certain families of land-owning Syrian Christians go through the ceremony of parboiling the rice in ancient stone vats in their backyards. During the several hours that the grain boils, they take advantage of the extreme heat within the vats to have a brief and passionate extra-marital affair with the coconut. The result is an exotic, lyrical dessert that you will be lucky to find only once a year, provided you are in the right Syrian Christian home at the right time.

The coconut should be well-chosen, neither so tender that the inner flesh is pulpy and loose, nor so mature that the white has hardened into a shell. Once such coconuts have been selected, a slice is neatly removed from the top, and the sweet water drained through the opening.

Each coconut is now stuffed with a delicious mixture featuring flattened rice (pohe in Mumbai, aval in Kerala), jaggery, a few cardamom pods, some jeera and a spoon of clarified butter). The coconut’s lid is now replaced, and the entire gizmo is bound up tightly with cloth — and tossed into the vat where the rice is boiling.

Here, in the intense heat of the cauldron, the treasure within the coconut is transformed by a process that is neither boiling nor baking nor entirely pressure cooking nor anything else. For a few hours, the coconut dances about in the water, like an impatient egg in an incubator. When the rice is finally parboiled, the coconut too is all set to deliver.

If you’ve done it right, according to Mohan, then you should be able to tear away the outer husk of the coconut, which would have tuned loose and fibrous. Sitting within it like a nearly perfect pearl, should be a hot, white ball filled with a heavenly sweetness. Through the hole in the top, you’d probably get wafts of cardamom, cumin and butter. You merely let it cool, and then serve it.

Mohan disappeared into Kerala’s dusk, and I never met him again. Back in Mumbai, I valiantly tried to recreate the Syrian Christian Coconut at a friend’s house, using a pressure cooker instead of a stone vat, but all I got was a misshapen pulp and a demolished coconut. Since then, I have collared many a Syrian Christian and asked them to tell me yea or nay about the Syrian Christian Coconut. They have all heard me out patiently; some have shaken their heads sadly; others have smiled tolerantly.

They didn’t say it, but I could tell they thought I was nuts.

A pulao with olives? February 21, 2007

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food.2 comments

That’s not the only surprise in store when Ishtiyaque Qureshi decides to take over the kitchen, discovers C Y Gopinath

ISHTIYAQUE QURESHI CONTROLS FOOD. The way a pet-lover controls his pet.

If he doesn’t want his onions to brown just yet, they will patiently await his further instructions. If he wants the meat not to stick to the bottom of the pan, then the meat will obediently float around in its oil, sticking not even to its closest friends. If he wants the garlic to go to sleep, it will go to sleep, pretending it’s actually an almond. To understand which djinn gave Ishtiyaque his awesome powers, you must go both into his genes and genesis. Genes first.

Ishtiyaque’s father, Imtiaz, was already a legend in the gullies of Lucknow before he was discovered by the Maurya Hotel group. In those bylanes, he had improved his own mastery of ingredients and proven his mettle in simple, nearly impossible feats — such as mixing sugar into rice. The accolade went to him who could mixing the largest quantity of sugar into cooking rice without sacrificing the flakiness of the final product. Imtiaz, the story goes, could effortlessly blend 3 kilos of sugar into a kilo of rice.

The architect of the famous Dum Phukt Restaurant — whose Bombay edition closed down after a bomb blasted the Searock Hotel — was hailed, on the inside flap of the menu, as being illiterate and unschooled, but that was wrong. Imtiaz’s studies were more precise than most engineers’ and more sophisticated than most artists’. And it was this extraordinary skill of mastery over the cooking process that he passed on to his eldest son Ishtiyaque, who never thought he’d one day be a virtuoso in a kitchen.

I asked to meet him after tasting his butter-like, utterly yielding kakori kebab, revived from the dhabas of Uttar Pradesh. As our acquaintance grew, I was privileged and delighted to be his guinea pig in a number of experiments. In one, he served me what seemed like an almond kheer, except that the ‘almonds’ were pods of garlic whose ego he’d subjugated by careful ministrations in simmering milk, converting them in the process into something quite nawabi and aristocratic.

On another occasion, he satisfied a picky vegetarian companion of mine with a stupendous biriyani which she promptly labelled a sham. But it was not. The ‘meat chunks’ were blocks of jackfruit, cooked so that their texture, taste and consistency was indistinguishable from mutton.

The third time, at the Leela Kempinski’s Indian Harvest, Ishtiyaque decided to experiment with morrels, the exotic and costly mushroom-like fungus that is so prized in French cuisine. He delivered an array of delicacies to our table, all Indian as they could be in taste, yet ineffably refined by the subtlety of morrels.

Now for the genesis. Ishtiyaque is one of the few unsung heroes of the Indian kitchen. He’s the maestro who will never be the witty host of his own food show on Star TV, the chef who will never write his You-Too-Cook-Be-Like-Me best-seller. In fact, this extraordinary artist shuttles around in the twilight zone between the cooking and the food processing industry. He disappeared for a spell to Bangalore, exploring the frigid world of frozen kebabs and biriyanis. Then, tiring of that, he re-entered normal life at the Leela Kempinski in Mumbai. Then there was another disappearance to Ahmedabad, another disenchantment, and another homecoming. You may see him today triumphantly re-inventing one of Mumbai’s most illustrious Mughlai restaurants. The Bandra edition of the Copper Chimney, renamed the Charcoal Grill, is currently a showcase of Ishtiyaque’s talents.

He made his olivon ka biriyani in my humble kitchen. In contrast to my panic-driven method of putting together my merely passable meals, Ishtiyaque cooks as though he had all the time in the world. The onions will not char while he turns away from them to play with my son. The meat will not separate into fibres because he was busy pounding garlic for the raita. With Ishtiyaque, cooking is an act of will, man against masalas, and the winner is always the same.

“But olives in a biriyani!” I exclaimed. Spain meeting Hyderabad, bullfights in the haveli, torreros and tandooris. How could they mix?

Ishtiyaque smiles. And that reminds me: until someone imported potatoes into India from South America, whoever had heard of batata wadas here?

Olivon ka Pulao

Ingredients

150 gms ghee

1/2 kg Basmati rice

2 Bay leaves

1 gram saffron

3 big cardamoms

3 small onions, thinly sliced

3 garlic cloves, crushed

3 green chillies

2” piece of ginger, julienned

Yellow chilly powder (to taste)

Salt to taste

50 gms fresh mint leaves

20-25 pitted green or black olives

Juice of lemon or 1 tsp aamchoor (dried mango powder)

5 gms garam masala

1 1/2 cups of soya bean nuggets (optional)

A generous fistful of dough

Method

1. Wash the rice clean in several changes of water, and soak it water until needed.

2. Heat ghee on a low fire, and brown the onion rings in it, stirring frequently until they are golden brown and crisp. Use a slotted spoon to drain the oil off the onions.

3. If you are planning to use soya bean nuggets, fry them light golden in a little oil, and keep aside.

4. To the same ghee, add the crushed garlic, bay leaves, big cardamoms, green chillies, ginger, and half a cup of water. Sauté for about three minutes. If you are using soya bean nuggets, add them now, and then add a litre of cold water, or enough to cover the rice. When the water comes to a boil, add the soaked rice and salt to taste.

5. When the water comes to the boil again, add the pitted olives, mint and saffron and stir it gently.

6. Using the dough, seal the rim of the cooking vessel and place the lid firmly against it. Put the vessel on a tava and let it cook on slow heat. When the steam begins hissing out through a weak spot in the dough, the pulao should be ready. If it is not, add a little more hot water, reseal the vessel, and let it cook a little longer.

7. When the pulao is done, garnish with the crisp fried onions, sprinkle with garam masala, and serve hot, along with a little raita.

The cauliflower becomes a real man February 21, 2007

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food.3 comments

The cauliflower has an identity problem but Suman Bakshi knows exactly how to solve it, says C Y Gopinath

YOU SURELY KNOW THE STORY of the poor, deluded cauliflower.

He tried to join the World Wrestling Federation, but was rejected on account of his ridiculous assertion that he should be treated as equal to beef. Claimed that though he had been plucked fresh from a vegetable patch, he had the soul of tenderloin.

This explains his current identity crisis. He feels macho yet curiously out of place when they marinate him in tandoori masalas and cook him along with seekhs and reshmis. On the other hand, he feels embarrassed but oddly at ease in a salad in the tittering company of baby corn and snow peas, all dressed in olive oil.

Most of all, the cauliflower is realising that without some cosmetic intervention — either complete immersion in some fancy French sauce or lots of garam masala — he will never be one of the boys. And this must be one of the reasons why cauliflowers, in season or out of it, are specially fond of Suman Bakshi neé Hattikudur, Mangalorean by heritage, Kashmiri by marriage, Mumbaiya by upbringing, a lady from neither here nor there and therefore at home everywhere, but particularly in her kitchen, where she casually re-incarnates old dishes into riveting new avatars.

For example, she’d added something devilish and tart to the cauliflower dish which I had christened Caulifornia after just one sampling.

“Aamchoor?” I asked expertly, but she shook her head.

Then what? Tamarind? Surely not. What was it? Suman ignored the question.

I first tasted Caulifornia some months ago out of a lunch box Suman had packed for her husband Jayant Bakshi. Now JB is not only is taller than Godzilla, but he comes from Kashmir and is a perfectionist who makes perfectly round chappatis. Which even Suman can’t do.

I knew, with my first mouthful of Caulifornia, that the phool gobi had finally become a somebody. An Oscar nomination was on its way.

I called up Suman and asked her whether she could make the dish for me.

“But which one do you mean?” she fretted. “I do so many different things to cauliflowers. Did it have tomato in it?”

No. But I remembered seeing bits of green leaves.

“They’d be cauliflower leaves. Was it red or —”

Definitely not red. Maybe no red chilly powder.

“Hmm. What about coriander leaves?”

I could not recall.

“If it had coriander, that would be a Kashmiri touch,” she said anxiously. “I change it around by adding Kasuri Methi leaves instead. Any paneer?”

Paneer and cauliflower? I was mortified. “No,” I said evenly. “Definitely no paneer. But green peas, yes.”

We couldn’t reach consensus on which cauliflower version had captivated me that day months ago, so Suman put together two entire cauliflower entreés, just in case. In the second one, the cauliflower is pressure cooked whole, immersed upto its ankles in a mesmerising tomato gravy. I named that dish Don Cauleone, but that was definitely not the cauliflower of my dreams. That honour went to Caulifornia.

Caulifornia is not a quickie dish. It has Kashmiri touches, such as the soont (dried ginger powder) and saunf (aniseed) powder. It also has a tangle of spices, with a little bit of everything — or so it would seem. But it is my considered insight that the trick is in the ginger and aniseed powders, the Kasuri Methi, and the browning of the cauliflower before the show starts. If you try it at home, and you should, then do remember that it connects outstandingly with hot chappatis and some plain, garnish-free masoor or tuvar dal.

“So,” I said, licking my fingers. “What’s the little extra you added which gave it that sharp undertaste?”

Suman looked distinctly uneasy. You see, she understands the cauliflower’s predicament: he hates dressing up. He likes to be seen with the boys, do the manly thing, even though he feels more at ease with the ladies in the beauty parlour. And now here Suman had dressed him up in saunf and dried ginger powder and made a proper parlour queen out of him. This is why, I now believe, in a fit of utter thoughtfulness, she tossed in a full teaspoonful of Dijon mustard paste along with the dried spices.

And thus converted the cauliflower from being a low, limp-wristed cousin of the cabbage to sheer majestic royalty.

Caulifornia

Ingredients (to feed 4)

500 gms cauliflower

250 gms paneer

Half cup curds

2 green chillies finely chopped

1″ ginger cut into fine shreds

1/4 tsp hing (asafoetida)

Powdered spices

1 tsp jeera (cummin seeds)

1/2 tsp haldi (turmeric)

1 tsp jeera (cummin) powder

2 tsp dhania (coriander) powder

1 tsp soont (dried ginger powder)

1 tsp saunf (aniseed) powder

1 level tsp Kasuri Methi leaves

Vegetable oil for frying and cooking

Salt to taste

Garam masala: Grind together

1 big elaichi (cardamom)

1/4 tej patta (Bay leaf)

1” dalchini (cinnamon)

5 laung (cloves)

5 elaichi (green cardamom)

Some jaiphal (nutmeg) scrapings

5-6 whole black peppers

Method

1. Choose a fresh, firm cauliflower with crisp green leaves. Keep the leaves aside after washing them thoroughly. Cut the cauliflower into big flowers, including about an inch of the stem with each flower). Wash thoroughly and then soak in salt water for about 15 minutes to flush out worms, if any.

2. Heat oil about an inch deep in a frying pan, and deep fry the cauliflower until they turn lightly golden. Place them on kitchen paper to drain the oil thoroughly. If you are using cauliflower leaves, fry them separately for a few seconds in the same oil.

3. Cut the paneer into squares of 1.5 inches and 1/4” thickness. Fry them briefly in very hot oil, until they begin turning light brown. Remove them with a slotted spoon, letting the oil drain out, and keep them in a bowl of cool water.

4. Heat half a cup of vegetable oil in a kadai. When the oil is very hot, add the hing. After a few seconds, add the finely shredded ginger, stir briefly, and then add the jeera (seeds). As they begin browning lightly, add the green chillies. Mix the curds in, and stir briskly till all the moisture has been absorbed.

5. Add half a cup of water and cook for about 2 minutes on a medium fire. Add the cauliflower, the Kasuri Methi, the garam masala, and another half cup of water. Add the paneer, and turn gently with a wooden spatula, so that they absorb the gravy. Cover and cook for about 10 minutes, or until the cauliflower are cooked though still crunchy. The gravy should be thick and moist.

NOTE: Peas may be used instead of paneer.

Don Cauleone

Ingredients (to feed 4-6)

1 large cauliflower

2 tbsp tomato pureé

2 tbsp chopped coriander leaves

1/4 tsp hing (asafoetida)

2 tsp cornflour

1 cup milk

Whole spices

1” dalchini (cinnamon)

5 laung (cloves)

5 elaichi (green cardamom)

5-6 whole black peppers

1 tsp whole jeera

Powdered spices

1.5 tsp Kashmiri red chilly (degi mirchi) powder

1/2 tsp haldi (turmeric)

2 tsp jeera (cummin) powder

2 tsp dhania (coriander) powder

1/2 tsp sugar

1 tsp garam masala (see recipe for Caulifornia)

Vegetable oil for frying and cooking

Salt to taste

Method

1. Trim the cauliflower, discarding the leaves. Cut the stem, creating a flat base, so that the cauliflower will sit straight. Soak in salt water for 15-20 minutes to flush out any worms and insects. Drain and dry, and then deep fry in about 2 inches deep oil, turning it over carefully so that it browns on all sides.

2. In a pressure cooker, transfer a half cup of the oil in which you fried the cauliflower, and heat it. When it is very hot, add the hing, followed by the whole spices and the jeera. A few seconds later, add the tomato pureé and continue frying till the oil separates from the tomato. Now add the powdered spices and sugar, salt to taste and half a cup of water, and let it come to a boil.

3. Stand the cauliflower upright into the pressure cooker, sprinkle chopped coriander leaves over it, and add a cup of water. Replace the lid and pressure cook for 1 whistle, let it cool, and open it.

4. Make a solution of the cornflour and a little milk, and add it to the gravy, followed by a cup of milk. Stir to thicken the gravy somewhat while bringing it to a boil.

5. To serve, carefully transfer the cauliflower to a dish, and pour the gravy over it. Just before serving, streak the dish with cream and a sprinkle of garam masala (see recipe for Caulifornia).

The search for gnocchi February 18, 2007

Posted by C Y Gopinath in Food.2 comments

Even if you can’t pronounce it, you can’t stop it from being a surefire hit, says C Y Gopinath